There are the trips not taken, the routes not followed, and the timetables that cannot be worked out. I rarely write about my stillborn sojourns. It is painful to recall aborted plans that started with hope and ended in hopelessness. These chances not taken can be summed up as an inversion of the famous Sinatra lyric from My Way, “Regrets, I’ve had a few…too few to mention” into “Regrets, I’ve had many, too many to mention.” My way ended up being the wrong way.

What worries me the most about my itinerary for the lost cities beyond the borders of Hungary is that it will never come to fruition. That is why I have tried to trick myself into believing the itinerary is for armchair travel only. Nevertheless, my underlying and unspoken aspiration is to make this dream become reality. The reason it might not is a matter of time. As I plan this potential journey, I am becoming acutely aware just how much time plays a part in the choices I make while traveling in Eastern Europe.

Managing time – Oradea City Hall Tower

Road Weary – Crossing The Upper Tisza

There is Eastern Europe, and then there is far Eastern Europe. I define the latter as places in the region that are remote from the popular tourist routes. The westernmost stretch of the Ukraine-Romania border is one of them. I consider this to be the wildest of the wild east. This is not just because of both countries’ association with some of the most volatile European history since the beginning of the 20th century, it is also because a stretch of the border is naturally demarcated by the Upper Tisza River. When I learned this a decade ago, it astonished me. My image of the Tisza had been informed by numerous crossings of the river on the Great Hungarian Plain. I had always thought of the Tisza as a broad, languid river flowing through flat land as it heads south to feed the Danube. That was until I saw photos of the Upper Tisza along the Ukraine-Romania border that showed a narrower, faster flowing river. The photos led me to daydream about one day crossing this natural border.

While developing my Lost Cities itinerary, I thought that there might be an opportunity to cross the Upper Tisza when I traveled from Uzhhorod to Oradea. That was until I looked closely at a map and noticed that the Ukraine-Romania border was to the southeast of Uzhhorod, whereas Oradea was directly to the south. Trying to find a way to cross the Upper Tisza between Oradea and Uzhhorod would require a detour. On the map, this detour did not look that difficult, but railways in the area are few. Roads are often the only option. I have been on enough to-lane highways in Ukraine and Romania to know that traveling on them is time consuming due to their narrowness and condition. Despite these drawbacks, I researched a potential trip routed through the small city of Satu Mare in northwestern Romania.

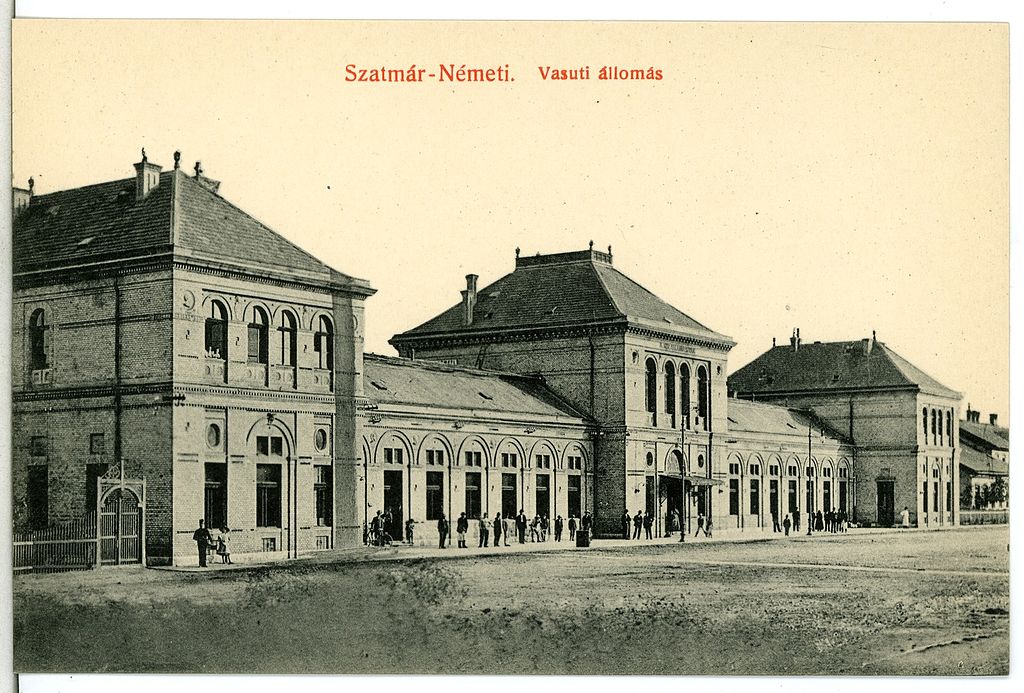

The place to be – Satu Mare Railway Station in 1911

(Credit: Brück & Sohn Kunstverlag Meißen)

Clock Watching – Taking My Time

Bus travel in the remoter reaches of Eastern Europe is often the only means of transport. That is the case for anyone looking to get from Uzhhorod to Satu Mare. It requires two potentially exhausting bus rides. That is followed by a three-hour train journey between Satu Mare and Oradea. All this adds up to at least a twelve-hour journey. Timeliness is not the strong suit of public transport in Romania. Neither is a border crossing from a country at war, to one that is a member of the European Union. Specific travel times are rendered meaningless. The best that can be hoped for are rough estimates of arrival times. In this context, a couple of hours can easily double. For this potential journey, time was working against me.

Sitting in an armchair months or years away from an actual trip between Uzhhorod and Oradea, it is easy for me to delude myself into believing anything might be possible. Pushing the boundaries of endurance is appealing from a distance. I know from experience just how different reality can be, especially when bus travel is involved. I love riding on trains because I find even the worst ones to be more comfortable and relaxing than traveling on a bus. The trains I have been on in Ukraine and Romania are slower than buses, but they have everything else to recommend them. For instance, on a train I can stretch my legs while not worrying about the numerous near misses that occur on bad roads with drivers who love to risk everyone’s life. Furthermore, I do not have to sit in cramped quarters among fellow passengers whose clothes are permeated with the smell of cigarette smoke. Avoiding these annoyances makes the slower pace of train travel more tolerable.

There is also the historical accuracy that comes with train journeys to the lost cities on my itinerary. When Uzhhorod and Oradea were known as Ungvar and Nagyvarad in Austria-Hungary, those who traveled to them would have done so by train. Contemporary railway lines still follow much of the network laid down by the Hungarian National Railways network during the last half of the 19th century. Taking trains offers me an opportunity to follow the exact same routes in many cases. I am seeing the same landscape, as citizens of the empire saw it over a century ago. It is possible on these journeys to relive a semblance of the past while traveling at the same speed as citizens of the empire did long before me.

A New Direction – Puspokladany Railway Station (Credit: Aspectomat)

Mental Sanity – A New Direction

My love for train travel led me to decide that my best bet for efficiency and mental sanity will be to travel in a straight shot south from Uzhhorod to Oradea. This will not be easy. Traveling through rural areas that have changed little since the days of Austria-Hungary takes patience. The one thing that has changed is national borders. This inevitably leads to delays. Add to that, the usual issues with poor infrastructure found in some of the poorer parts of Eastern Europe and my journey from Uzhhorod to Oradea will either be an adventure or a nightmare. In this case, probably both. I began researching more straightforward and expedient options for the journey. This led me in another bizarre direction, the town of Puspokladany in eastern Hungary.

Click here for: The Long Haul – An Exhausting Journey To Oradea (The Lost Cities #6)