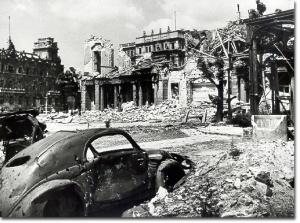

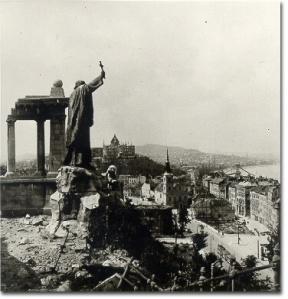

As the siege came to its final, tragic end, Budapest, the “pearl of the Danube” was largely in ruins. Famed Hungarian author Sandor Marai left this impression, “What I see is at first sight horrifying, but after every hundred meters becomes more and more grotesque and improbable. The mind boggles. It is as if the wanderer were passing not through city districts but through excavations. Here is a wall of a building where a friend used to live, there the remnants of a street, in Szell Kalman Square the wrecks of streetcars and then the devastation of Vermezo Meadow, Naphegy Hill and the Castle.” Marai’s words recapture a surreal, otherworldly moment seared into the city’s consciousness by the all-consuming flames of total war.

The Great Forgetting

Ironically, the siege and ensuing battle for Budapest are hardly spoken of today. It suffers from a case of historical amnesia. It has been nearly forgotten by popular historians, but physical evidence in the form of bullet and shell holes is still readily apparent to the discerning eye.

So why is the siege relatively unknown? Well for one, there were more famous, but not greater battles to come. The battles for Vienna and Berlin were respectively six and fourteen days in length. Compared to the fifty-one day siege of Budapest those battles lasted for a short period of time. Consider also, that the fighting in Vienna and Berlin would not have concluded so quickly without the huge loss of German forces during the siege of Budapest. The Germans bought time for themselves with their futile defense of the city, but it came at so high a cost that later battles were over relatively quickly due to a lack of manpower and weaponry.

Another reason for the relative anonymity of the battle is that there were really no famous figures that met their fate here. There was no Hitler shooting himself in a bunker, only thousands of common soldiers slowly expiring beneath the streets of Buda. There was no General Zhukov creating a historical legacy on the rubble of the Reich, only men with such forgettable names as Malinovsky, men who history would soon forget, but who led the Soviets to victory in the most terrible war ever known to mankind.

A Battle That Should Have Never Been Fought

And finally, there were really no heroes to proclaim. The siege of Budapest was a battle that should have never been fought. The Hungarians, whose capital had been sacrificed, did not want it. The common German soldier was not allowed to surrender, only sacrifice – first their Hungarian allies, but in the end, also themselves. And the Soviet’s would gladly have accepted a Hungarian armistice and bypassed the whole horrific affair. Their designs lay further west, Hungary was a land that had to be crossed, but ended up as a prolonged battle that never should have occurred.

The Soviet commander of the 2nd Ukrainian front, Rodion Malinovsky, furious at the protracted fighting, is said to have told the German commander Karl Pfeffer-Wildenbruch following his surrender, “If I weren’t obliged to account for your head in Moscow, I’d have you hanged in the main square in Buda.” Many others were not as lucky. The Soviets took revenge on those who had slowed their drive westward. They also imposed their will on the Hungarian people over the months, years and decades to come.

Places to visit: Marai Memorial plaque on his former home at Miko utca in Buda, District 1, Krisztinavaros.

Sources: The Siege of Budapest: One Hundred Days in World War II, Kristian Ungvary, Yale University Press, 2006.

Specifically: Chapter Six, The Siege and the Population, pgs. 257 – 373

Epilogue, pgs. 374 – 380.

Memoir of Hungary, Sandor Marai, Central European University Press, 2001.

Marai quote from A Walk in Buda, Budapest, Sandor Marai, December 1945.

Malinovsky quote from: The Siege of Budapest: One Hundred Days in World War II, Kristian Ungvary, pg. 376.

Fortepan.hu