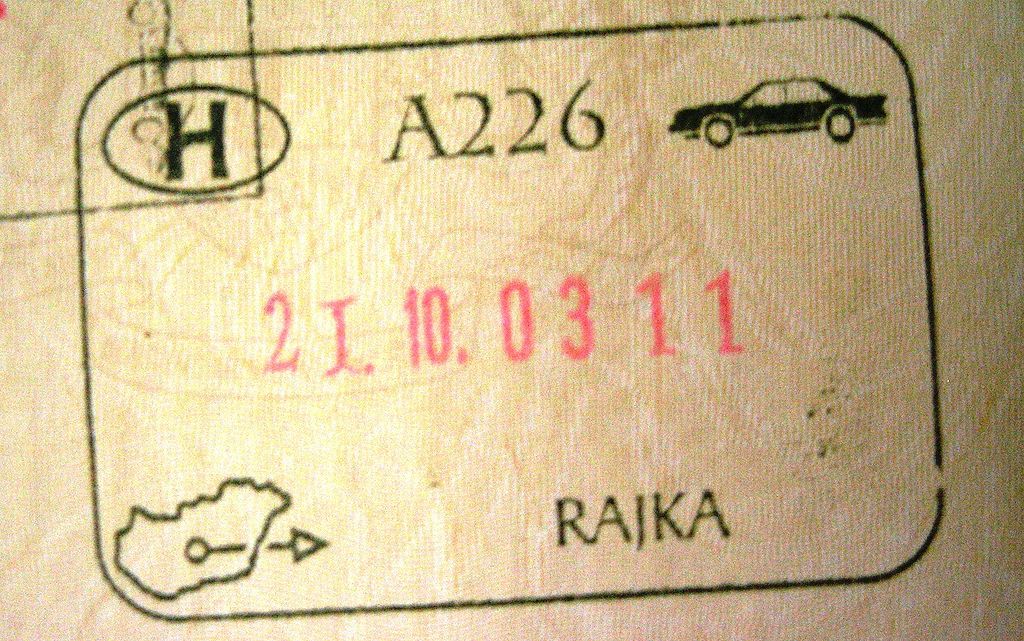

I find myself repeatedly going down the rabbit holes of history while developing my itinerary for the lost lands beyond Hungary’s borders. While researching one place, I discover another, and that leads me to still another. Then I look back and can barely remember where I started. That is not a bad thing. Getting lost can lead to new adventures. This is what happened with my choice to visit Rusovce in Slovakia. I did not realize that it was so close to the Austria-Hungary-Slovakia tripoint. This led me to research the nearby villages of Deutsch Jahrndorf (Austria), Jarovce (Slovakia) and Rajka (Hungary). As I plunged deeper into each village’s history, I forgot what brought me to Rusovce in the first place. That is until now. Rusovce, Jarovce, and the village of Cunovo were taken from Hungary at the post-World War II Paris Peace Conference and given to Czechoslovakia. None of the villages seemed to hold much value except for their location near the Danube. The reason they ended up on the other side of Hungary’s border says a lot about the fear and insecurity that was pervasive in Czechoslovakia after the war.

Bridging the divide – Danube River at Bratislava (Credit: Rios)

Buffer Zone – Territorial Ambitions

Forgetting history is often seen as a negative. The main reason why is summed up by the famous quote, “those who forget history are doomed to repeat it.” Yet sometimes forgetting history can be a sign of success rather than failure. This occurs when problems that were once acute have either been solved or faded away. One example of this phenomenon in the lost lands is especially instructive. Most people in Slovakia and Hungary are unaware that a sixty-two square kilometer piece of land on the fringes of Bratislava was given to Czechoslovakia after World War II. That land included the villages of Rusovce, Jarovce, and Cunovo. This was done to expand the Bratislava bridgehead, a military necessity at the time that is no longer needed today. Furthermore, the bridgehead is unlikely to ever be needed in the near or distant future because Slovakia and Hungary are now both members of the European Union. Border control between the two countries has been dismantled.

Despite periodic upticks in tensions between Slovakia and Hungary the chance they will have an armed conflict is virtually nil. There is also very little threat to Bratislava from the other countries that border Slovakia. Austria is peaceful and prosperous. Poland has no designs on Slovakian territory. Neither does Ukraine. The war between Ukraine and Russia has damaged Slovakia’s relations with both, but it is highly unlikely to ever have any effect on its territorial integrity. The upshot of all these developments is that the Bratislava bridgehead has faded into obscurity. That was not the case at the Paris Peace Paris Conference in 1946-47. Europe in the aftermath of World War II was a mess. Fear and insecurity were rampant. Considering the context, it is easy to understand why. Czechoslovakia had been dismembered in 1938 at the behest of Nazi Germany. The Hungarian government had joined in to get southern Slovakia back under its control. Nazi Germany took what was known as the Bratislava bridgehead for themselves.

Displacement – Old manor house in Cunovo (Credit: Izzino25)

Strategic Imperatives – Protecting Bratislava

In military terminology, a bridgehead is a position on an enemy’s territory separated from one’s own territory by a body of water. It offers tactical and strategic advantages to the holder. They can move soldiers and supplies over the water to enhance military operations. The Bratislava bridgehead had allowed the German military to control a vital transport artery across the Danube. After World War II ended, the Czechoslovaks wanted to ensure they had an expanded bridgehead to protect Bratislava in case of another war. The city was vulnerable because of its proximity to the Hungarian border which was just across the Danube. Moving Hungary’s border further away from what was the largest city in the Slovak half of Czechoslovakia was a top priority during treaty negotiations in Paris.

The Czechoslovak delegation asked for five villages in Hungary to create a larger buffer zone between Bratislava and Hungary’s borders. Those who negotiated in support of the bridgehead felt it was vital for national security. The military ramifications of the bridgehead were obvious. There were also economic implications. Czechoslovakia’s largest port was on the Danube at Bratislava. With the bridgehead, the port would be protected. It could also be expanded. This would help drive badly needed postwar economic development. The victorious powers agreed with the Czechoslovak arguments. The result was that Czechoslovakia received three of the five villages they asked for in the negotiations.

The Hungarian villages of Oroszvar, Horvathjarfalu, and Dunascun became Rusovce, Jarovce, and Cunovo in Czechoslovakia. Most of the Hungarian inhabitants of these villages were displaced. Large numbers of Slovaks would soon move into them. The territorial adjustment was small but effective. Czechoslovakia’s border with Hungary had been stabilized. The only change to the area since then was after the Velvet Divorce occurred in 1993 as the Czech Republic and Slovakia became separate nations. Slovakia inherited the bridgehead. By then its military importance had waned. The three villages are now part of the larger Bratislava area. They are valued real estate for those who want to live in a more rural environment and commute to work in the city.

Out of the way – Abandoned border crossing at Jarovce (Credit: Bratislavcan85)

Shared Interests – Beyond The Bridgehead

Today, the Bratislava bridgehead is a historical footnote. A 2007 article in the Slovakian newspaper SME detailed how younger generations of Slovakians knew nothing about the bridgehead. The concept can be hard to grasp for anyone who did not suffer through World War II. The bridgehead was a matter of national insecurity following the war, The Czechoslovaks did not trust the Hungarians, and the feeling was mutual. Trust could only be built after decades of peaceful relations. By then, the Bratislava bridgehead was forgotten. except by the elderly and history buffs. Slovakia’s frontiers were no longer vulnerable. The Bratislava bridgehead had lost much of its reason for being. This was the best possible outcome for all involved. Economic affairs rather than military ones are now central to relations between Hungary and Slovakia. Both sides have a shared interest in moving beyond the past. Forgetting the Bratislava bridgehead is a step in the right direction.

Click here for: Unexpected Guests – The Croatians of Jarovce (The Lost Lands #40)