Listen to the audio cast: The End of One War And The Start of Another – The Siege of Budapest Tour (Part Ten – Conclusion)

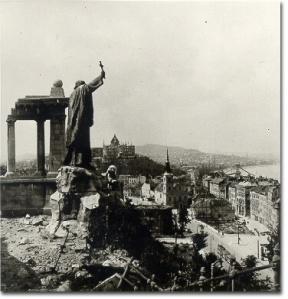

In 1947 the Liberty Statue (Szabadsag Szobor) was constructed atop Gellert Hill close to the Citadella. It occupies not only a prominent place in the city, but also an ironic place in Hungarian history, both physically and literally. Ironically, because Gellert Hill, is a place where the last two historic occupiers of Hungary, the Austrians and Soviets decided to display an imposing symbol of their rule. The Citadella, directly behind the monument, is a fortress built by the Habsburg Empire following the failure of the 1848 Hungarian revolution. It was representative of Austrian rule over the Hungarian people.

Liberation By Occupation

Likewise, almost a century later, the Soviets placed the Liberty Statue near the same spot. Throughout most of the latter half of the 20th century, anytime Hungarians gazed upwards from the lower parts of their capital city, they would see the so called “Statue of Liberty” holding a palm leaf in her hand. The palm leaf was meant to symbolize peace, but it meant something quite different. Lady Liberty might as well have been holding a hammer or sickle instead. The monument was really not about liberty, instead it was about occupation. The Soviets had gained control of the city at great cost, over 200,000 casualties, during the siege of Budapest. They had no intention of losing that control.

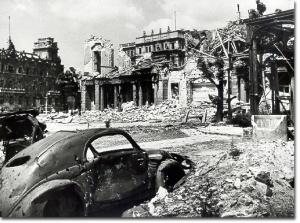

The Liberty Statue was one of the more innocuous symbols of Soviet rule. After all, following the surrender, the Soviets had imposed their will as they saw fit. An alarming degree of violence and lawlessness tormented the population of Budapest long past the end of the war, into the next year. Soldiers shot prisoners, both POW’s and civilians. Thousands of women were raped. National treasures owned by the Hungarian people were looted from vaults. One war had ended and another had just begun. This would be a war for the soul of the Hungarian nation.

A Monument Survives, Its Meaning Changes

If that was not bad enough an insidious communist dictatorship arose right along with the Liberty Statue. Thousands of innocent citizens were imprisoned, sent to forced labor camps, tortured or executed. In 1956, just eleven years after the siege came to an end, the Hungarian people rebelled against this dictatorship. But the revolution attempt failed while thousands perished and even greater numbers emigrated to the West. It was not until 1989, when the communist yoke was finally thrown off, that the Hungarian people would finally be able to once again freely rule themselves.

Not long thereafter, the wording on the Liberty Statue was changed as well. It had said, “To the memory of the liberating Soviet heroes [erected by] the grateful Hungarian people [in] 1945.” After the iron curtain was torn down, the wording changed, “To the memory of those all who sacrificed their lives for the independence, freedom, and prosperity of Hungary.”

There was and still is talk today of having the monument removed once and for all. Yet it has survived, just as the Hungarian people have survived. Eventually this monument will crumble, but the nation of Hungary will still be standing, the ultimate survivors.

Indeed survival is a recurring theme in the history of this city, this nation and of the Hungarian people. A healthy respect and understanding of their history during the Second World War will help the nation not just survive, but also to thrive. Respect for the sacrifices and suffering of their countrymen and women – some who still walk the streets of Budapest today – who lived through the siege. And also, an understanding that the highest price of World War II, was the loss of freedom and independence for the Hungarian people.

Places to visit: Gellert Hill, Liberty Statue, Citadella

Sources: The Siege of Budapest: One Hundred Days in World War II, Kristian Ungvary, Yale University Press, 2006. Specifically Chapter Six, The Siege And The Population, Life Goes On, pgs. 363 – 373.

Every Statue Tells A Story: Public Monuments In Budapest, Bob Dent, Europa Konyvkiado, 2009, pgs. 258 – 263.

Twelve Days: The Story of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, Victor Sebestyen, Vintage Books, 2006, Chapters 3 & 4, pgs. 20 – 33.