Habit is a powerful force, perhaps the greatest force that governs our lives. It has been said that humans are creatures of habit. That truth cannot be emphasized enough. Habit brings order to the chaos of a world that constantly threatens to upend our lives. It acts as a source of comfort and security. Familiarity sets us at ease. Do the same things, the same way long enough, and habit becomes second nature. Habit is something you can rely upon. Friends and family may come and go, but habit remains with us for as long as we adhere to it. Habits are so comforting that they are hard to break. I discovered this as I planned the next stop on my itinerary for the lost lands beyond the borders of Hungary. I was left with a choice, go to either Transylvania or into the unknown.

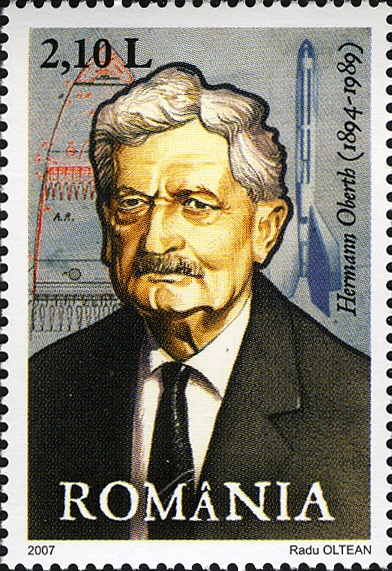

The railroad to Satu Mare (Credit: ticsung)

Easy Ways Out – Paths of Least Resistance

Travel should be the antithesis of habit. It is supposed to take us away from the dullness of our daily routines. Travel should help us get outside of ourselves and our self-contained worlds long enough to experience something exciting and new. Travel is supposed to be an adventure, not a repetition. And yet I know from experience how habits can influence travel. Waking up in a strange land, among unfamiliar surroundings, where I cannot speak more than a few words of a foreign language sends me fleeing back to the familiar.

When I am fearful, a habit of taking the path of least resistance begins to govern my actions and decisions. While planning the itinerary, I found myself mentally falling back on habit not long after crossing the border into Romania. I began to veer towards a preexisting pattern. First, I would cross the border at Letavertes-Sacueni like I did six years ago, take a rural highway to Alend, then wind my way up and over King’s Pass into Transylvania. This route was identical to the one I had taken six years before. I was semi-consciously following my own footsteps. The route did not excite me, but it was familiar and safe.

Once in Transylvania, I would have familiar choices for my other destinations. Cluj, Sighisoara, Sibiu, and Targu Mures, all cities I had visited before. I thought each place would help me learn about the Treaty of Trianon’s legacy. On those initial visits I was not focused on Trianon. Now I would be, with the added benefit of understanding what travel to each city entailed. This could make a potentially difficult journey much easier. I was practicing the art of self-delusion. A return journey comforted rather than intrigued me. This reminded me of returning to where I grew up. The luster might have worn off, but I would find contentment. That is what I wanted to believe. I hardly ever go home because I outgrew it long ago. The familiar went from being fascinating to unfathomable. Everything looks the same and has somehow changed. The same would be true in Transylvania.

Still, I tried to convince myself otherwise. I told myself that Transylvania was the most obvious choice to investigate the lessons of Trianon. It was the largest region of the lands Hungary lost. Hungarians went misty eyed, got angry, or became sullen (sometimes all three) when talking about it. What would a journey in search of Trianon be without Transylvania? Counterintuitive and shocking. Both of those appealed to me. Impulsively, I turned away from Transylvania. It was like walking away from a beautiful bride at the altar. I felt powerful rather than powerless. By defeating the urge for Transylvania, I was ready for a real adventure. There was still one other mental barrier to overcome.

A distant figure – Statue in Satu Mare (Credit: Elek Szemes)

On The Contrary – Coming To Crisana

I have never cared much about what other people think, but my sudden turn away from Transylvania led me to believe that in the future I would be forced to justify this journey to others. Someone would ask me, “What did you think of Transylvania?” My reply would consist of a blank stare, averting the eyes, and muttering, “I did not go there.” That would be followed by a deep and penetrating silence from my interlocutor who would silently be saying to themselves, “Are you kidding me?” Going to Transylvania is like marrying a millionaire. You might end up regretting the relationship, but the memories will be worth it. Nevertheless, I pride myself on doing the opposite of what is expected. My mother has told me on numerous occasions that I enjoy being contrary. The idea of resuming my contrarian persona energized me. I wanted to break my habit and set myself free.

I now contemplated Crisana as my new destination in Romania. I had been there before, but never spent a single night in the Romanian part of the region which encompasses the northwestern part of the country. My experience in Crisana consisted of a day trip to Oradea, passing through Arad on the train, and traveling across the region to or from Transylvania. Crisana has been mostly a place on the way to somewhere else. It had never captured my imagination the way Transylvania did. This time I vowed to not let my less than enthralling previous experiences with Crisana stop me from going there. There was one place I longed to investigate there. The city of Satu Mare (Szatmárnémeti).

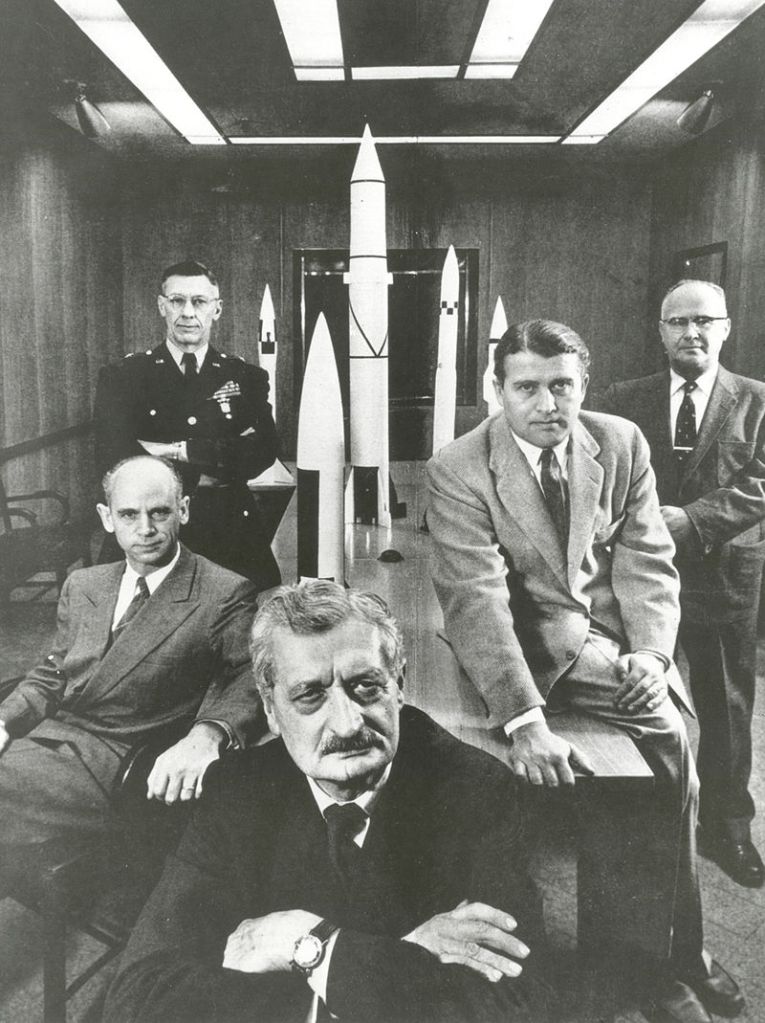

Icing on the cake – Dacia Hotel in Satu Mara (Credit: Roamata)

Relegation Zone – Sitting In The Corner

Satu Mare means “big village”. Picking it over the land beyond the forest (the literal meaning of Transylvania) was not an auspicious beginning. I knew a great deal about Transylvania, I knew nothing other than some demographic statistics about Satu Mare before and after Trianon. At least this was something to go on. The city surely had much more to offer. Satu Mare’s relative anonymity is nothing new for places in Romania. Like everything else in the country (except for the capital Bucharest), if it is not in Transylvania, then foreign tourists do not go there. Satu Mare’s location does nothing to help it. The city’s location in the northwestern corner of Romania does nothing to help it. Satu Mare is a regional transport hub of great value to local and regional travelers. It is not a destination for tourists, but it just might be for travelers. I intend to find out.

Click here for: Following The Bouncing Ball – Rediscovering Satu Mare (The Lost Cities #9)