A bestselling author working on his next book visits hundreds of museums across Central and Eastern Europe. He is looking for any artifact or exhibit that might increase his understanding of the sprawling Habsburg Empire which once stretched from northern Italy to western Ukraine. The author is interested in anything eccentric or unusual that he finds intriguing. This will inform his book which will be part history/part travelogue on a vast scale. With one of his trusty notebooks in hand and pen at the ready while visiting Sighisoara, Romania. The small Transylvanian city has much to recommend it. Most prominently, an Old Town – a UNESCO World Heritage Site – which rises above the rest of Sighisoara. The spires of several structures can be seen soaring skyward from a great distance. The most famous of these reaches crowns the Clock Tower.

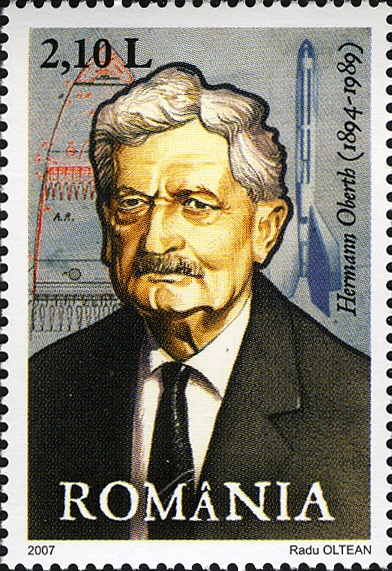

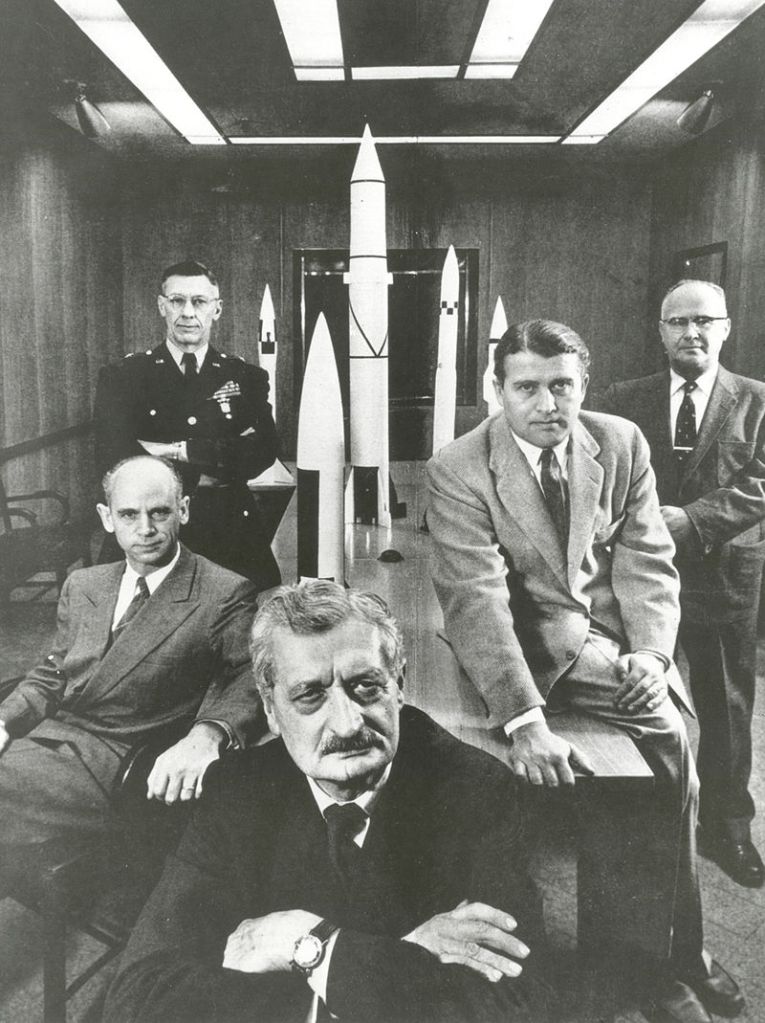

The author sets out to climb the 64-meter-high Clock Tower to get a bird’s-eye view of the surrounding Old Town in all its glory. Along the way he comes across an exhibit on the Transylvanian Saxon rocket scientist and spaceflight pioneer Herman Oberth. The author stops to have a look. He is fascinated by this odd exhibit improbably placed in a seven-hundred-year-old structure. He takes copious notes. This is not out of the ordinary for him. He has reams of such details lining the pages of his notebooks. The information from many of these notes will never make it into the book. Only those which are the most unique and make a larger point about the Habsburg Empire will find their way into print. That includes the exhibit on Herman Oberth in the Clock Tower.

Looking forward – Hermann Oberth bust in Sighisoara

Source of Fascination – A New Chapter

I am not a bestselling author, nor do I carry notebooks with me while visiting museums or historic sites in eastern Europe. I do carry a smartphone which I will sometimes use to take notes on intriguing people, places, incidents, and exhibits that I come across while traveling. When I visited the Clock Tower in Sighisoara, I took some photos. Unfortunately, all but one of them were lost several laptops ago. I must rely on photographic memories of what I saw during my visit. I found the exhibit on Hermann Oberth a source of fascination. Years later when I recalled seeing it, I wondered if my memory had been playing tricks on me. An icon in rocketry celebrated in a building constructed during the Middle Ages. Yeah whatever. Who would believe such a thing? Perhaps a person who has visited one too many underfunded museums. Lack of money has given many museums license to go in odd directions.

I have been in enough provincial museums to know that items of dubious historical value often end up in the exhibits. The Clock Tower in Sighisoara felt different. The tower was the museum for me. The artifacts on display were of minor interest at best. Climbing the tower was the only experience that would do. Nothing else could compare. At least, that was what I thought. There would certainly be no need to include an exhibit about someone not associated with the tower such as Hermann Oberth. The exhibit on him would have been better off in the Sighisoara History Museum, but the tower doubled as that museum. This left me bemused. I was not the only one.

A decade after my visit to Sighisoara, Oberth came back to me. Between 2014 and 2024, he lingered in my subconscious until one day curiosity got the best of me. While doing research on Oberth, I glanced across my living room at a bookshelf stacked with volumes I keep outside of my library and close at hand. Most of these are used as ready references. The books also act as eye candy. I love looking at the colorful spines of the (mostly) soft cover books. One of these will often catch my eye, tempting me to pull it from the shelf. On this occasion, it was the white spined Danubia: A Personal History of Habsburg Europe by Simon Winder. Danubia is a book I have read from cover to cover and often return to as a source of inspiration. Winder traveled all over what was once the Habsburg Empire. He spent most of his time there visiting hundreds of museums and historic sites in countless places. These visits are woven into the narrative fabric of Danubia. Winder’s observations are funny, illuminating, and provocative.

Great Read – Danubia: A Personal History of Habsburg Europe by Simon Winder

Historical Justice – Sins of Omission

I pulled Danubia from the shelf and instinctively searched the index looking for references to Sibiu and Sighisoara. Both cities are associated with Oberth. I was looking for information and inspiration about Transylvania. The handful of pages on Sighisoara immediately caught my attention because the Clock Tower exhibit on Hermann Oberth featured in them. Winder had seen the same exhibit I did. He too viewed it as a sublime piece of history found in an improbable place. The subtitle in the chapter dealing with the exhibit is “Transylvanian rocketry.” That is bound to get the reader’s attention. Unfortunately, many other subjects explored in museums do not. Winder talks about the bizarre exhibits that can be found in the museums of Eastern Europe. He creates a fictitious scene where the dullest exhibition case award is given at the annual Christmas dinner for museum directors in western Romania. Winder’s choice goes to an exhibit of two books in the Sighisoara Museum with “illustrations of a man demonstrating a back strengthening device.” For good reason I do not recall this exhibit.

Mania for museums – Simon Winder

I have experienced the same befuddlement as Winder at provincial museums in Eastern Europe. Artifacts that should never see the light of day are on display. It is anybody’s guess why. Perhaps because the museum does not have better artifacts, or the museum director has made a deliberate choice to avoid controversial historical topics. This is particularly true of recent history. The past in Eastern Europe is never far away. Memories and wounds are still raw. Better to stick with absurd therapeutic devices then delve into the 20th century. Even Hermann Oberth was a controversial subject. His work on V-2 rockets helped lead to the deaths of almost 3,000 British civilians. There was nothing about that in the exhibit. For all anyone knew, a local boy had succeeded beyond the wildest expectations. As Winder says, “Oberth was a terrible figure in many ways but from his mind stepped most of the basic principles of the space programme.” The exhibit did not do Oberth’s life historical justice, but it was still unforgettable.

Click here for: Reputation Management – Transylvania: The Land Beyond The Myth (Rendezvous With An Obscure Destiny #73)