A lightly trafficked road, farm fields interspersed with a few trees, a lone building set beside the road. This is the scene on an otherwise anonymous stretch of highway on the frontiers of eastern Hungary. The scenery gives no hint of what’s to come. Then the first signs appear for border control. Up ahead is a line all but invisible to the naked eye. That line has been the deciding and dividing geopolitical factor between Hungary and Romania for over a century. My anticipation rises as the car closes in on the border. The signs direct drivers to slow down and point to the proper lane. No border officer appears until the car comes to a halt. This is the experience that quickens my pulse more than any other while traveling. The expectation is that first there will be bureaucracy and then freedom. Everything depends upon a couple of officials I have never seen and will likely never see again. They are the gatekeepers to my future travels.

Remote control – Border crossing between Letavertes, Hungary and Sacueni, Romania

Initial Impressions – Locals, Lorries, & Limbo

I love remote border crossings in Eastern Europe. They give me the sense that after wandering in a linguistic and cultural wilderness that I have finally arrived. I define remote as any border crossing that is not along a major highway. Such border crossings are not hard to distinguish because they are in places few have ever heard of and fewer will ever go. They are mainly trafficked by locals and lorries. The highway will be two lanes until right before border control. This is the opposite of a heavily trafficked border crossing which has the look and feel of a travel plaza along a four-lane highway. There is a small army of serious looking border officers going about their business while masses of travelers wait in limbo. Delays can be lengthy and at busier times feel interminable. At remote border crossings officers take their work seriously, but they are less hurried in their processes and more relaxed.

Passing through the Hungary-Romania border always feels like an event to me. I get the sense that something important is about to happen. A remote border post causes my imagination to run wild. I would love to know how the officers feel about their jobs. What are their most dangerous and difficult duties? How are their interactions with locals from the opposite side of the border? In my more expansive moments, I can see myself working in solitude at such a post. Waiting for locals and wayward travelers to make the crossing. It is a thrill for me when the border officer comes out from a bland building. I try to put myself in their place. Meeting strangers who they only know by their documents and initial impressions. They are also standing on a historical fault line where the past is never far away. Their job is to make sure no one steps beyond the border line until they say so.

On the line – Border crossing between Artand, Hungary and Bors, Romania

Going Remote – A Sense of Destiny

While working on my itinerary to visit the lost lands of Historic Hungary, it did not take me long to realize that Romania would be my number one destination. Transylvania loomed large in that decision, but in its shadow lies Crisana. A region that includes large parts of eastern Hungary and western Romania. The latter still has plenty of ethnic Hungarians, especially near the border. Crisana is where I will enter Romania. The question is exactly where to cross the border. The choice will be based upon prior experience and personal preference. One thing I loathe is navigating a major border crossing. The busiest crossing between Hungary and Romania is Artand-Bors. The city of Oradea (Nagyvarad) is only a 15-minute drive beyond the border. I have crossed by both bus and car here before. The crossing is heavily trafficked by automobiles and lorries on both sides. The hectic pace can make for an irritating experience. The frenzied activity at Artand-Bors is not how I want to start my journey to the lost lands. I would much rather find a quieter and more remote crossing.

The solitude of a lonely outpost appeals to me. That sent me searching for an obscure crossing. One where the border officers do their work in relative anonymity. Fortunately, I have prior experience with one of these crossings, Letavertes-Sacueni. It received my full attention as I considered whether to add the crossing to my itinerary. Letavertes and Sacueni are backwaters, out of the way places that do not lend themselves to tourism. The big advantage the towns have is their proximity to the Hungary-Romania border. That is why I am choosing this as my first crossing. Traffic is bound to be light, border control is efficient, and wait times minimal. One of the more interesting aspects of crossing the border here is that the towns which give the crossing its name play a minor role for the traveler.

Running the border – A train and car on the Romanian side of the border in Sacueni

(Credit: Kabellerger)

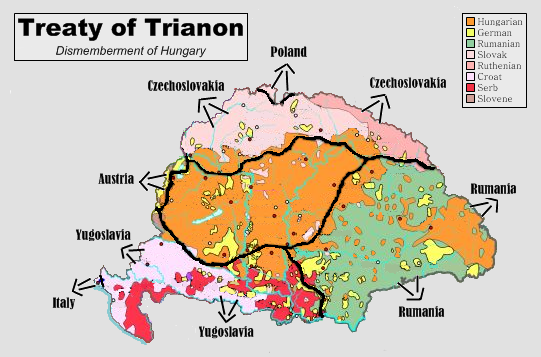

A Fine Line – Setup For Failure

I visited neither Letavertes (population 6,795) nor Sacueni (population 10,720) when I crossed the Hungary-Romania border there five years ago. From an ethnic standpoint, there is not much that separates the towns. Both are overwhelmingly populated by Hungarians. That is not surprising for Letavertes which is in Hungary. It is for Sacueni, where three out of every four inhabitants are ethnic Hungarians. There are twice as many Roma in the town as there are Romanians. I do not recall much about either town. Both places happened to be in the way of history in 1920 when the Treaty of Trianon took effect.

One thing I do wonder is why the border was drawn through this area. I have read extensively about the politics surrounding Trianon, much less so about exactly where and why the frontiers were drawn in a specific area. I assume that the lines on maps were informed by the opinion of “experts” at the Paris Peace Conference. Their on-the-ground experience with specific places must have been lacking. It makes little sense to put areas dominated by ethnic Hungarians on the edge of western Romania when Hungary was just over the border. Such points of contention were a recipe for strife. Both Hungary and Romania were being setup for failure. In retrospect, conflict was inevitable.

Click here for: All The Right Places – The Other Side of the Border In Crisana (The Lost Lands #5)