Provincial towns are not the standard settings for historical events. At least not in the popular imagination. The most important ones are made to seem like they occurred on a grand historical stage. In castles and palaces, on battlefields, and within major cities that are all larger than life. These are places that match in size and scale an event’s historical importance. The most popular parts of the past are rarely provincial. One of the reasons I fell in love with history was because it was a way to escape from the dullness of daily life in a small town. The idea that history would occur in a provincial backwater never crossed my mind. That belief was a false, and myopic view of history. Perhaps that is why I find it fascinating when I discover a history-making event that happened in a provincial town. Even if the event is more anonymous than famous, the fact that someone took the time to document it in a work of history is noteworthy. I discovered one such example while developing my itinerary for the lost lands beyond Hungary’s borders. This one involved the short-lived Republic of Heinzeland and the town of Mattersburg, West Hungary (now Burgenland in eastern Austria).

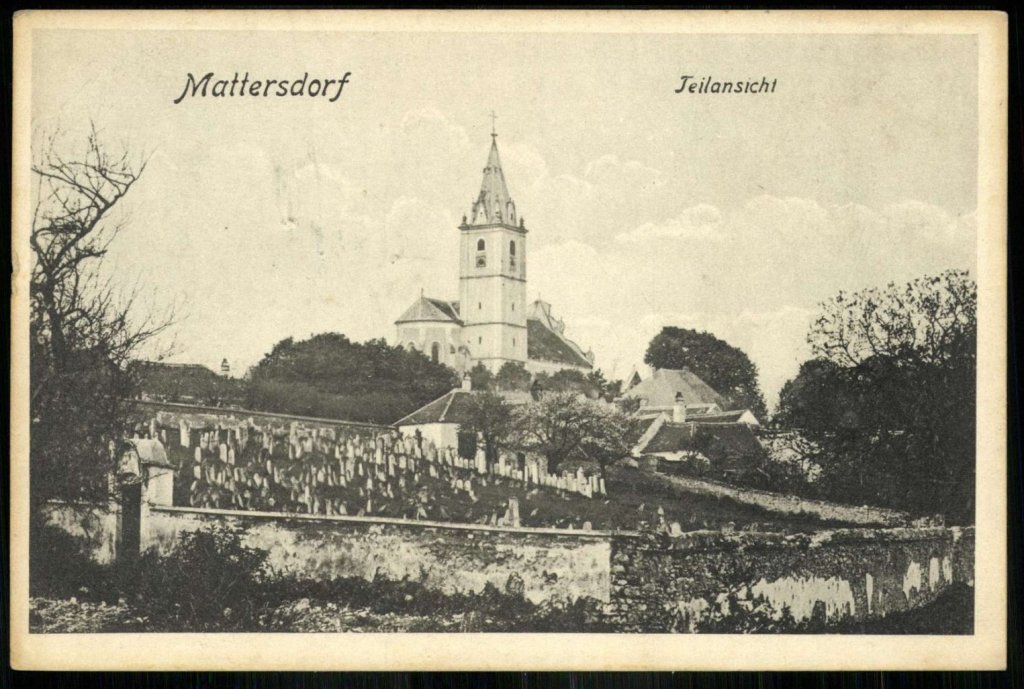

Waiting game – Mattersdorf in the early 20th century (Credit :Stadtgemeinde Mattersburg)

Future Uncertain – Declaration of Independence

In the final months of 1918, the newly formed Republic of German-Austria worked hard to bring West Hungary under its control. In this effort, pro-German-Austria propaganda was distributed throughout the region’s towns and villages to persuade the ethnic German population that it was in their best interest to join their ethnic kin. The locals were content to take a wait and see approach. This was the most prudent course considering that no one knew what the future would hold with the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s disintegration. The situation was chaotic and liable to change. Local advocates who wanted the region to join German-Austria made inroads with parts of the population. For example, ethnic German children in Mattersburg (Mattersdorf until 1924/Nagymarton in Hungarian) were reported to have tossed their schoolbooks onto the floor and began chanting “We do not want to learn Hungarian anymore.” Hungarian civil servants were also forced to flee the town due to threats of violence.

This was just the prelude to a bizarre and historic event that took place on December 5th when. Hans Suchard, a local politician and passionate pro-German-Austria advocate, declared the Republic of Heinzenland. This signaled that those in favor of German-Austria would go to extreme lengths to get their way. At the same time, Heizenland was a ridiculous proposition. The Republic was a political ruse more than a viable potential state. It was a way to move the region towards union with German-Austria. Suchard’s declaration did not have the force of law. Nor did it have any powers other than the ones Suchard and his supporters might declare. There was no upswell of public support for leaving West Hungary. Thus, the supporters of Heizenland would be forced to act on their own. The only way Heinzeland would have staying power was through force of arms. Weapons and ammunition were the preferred strong-arm tactics. To that end, weapons started being shipped into the region. The Hungarians intercepted one delivery. Another consisting of 300 rifles made it to Mattersburg. A showdown with Hungarian authorities looked imminent.

Sending a message – Postcard from Mattersburg in 1900

A Dangerous Idea That Made No Sense

No sooner did the supporters of Heinzenland begin to prepare for military action than the Hungarian authorities acted. They sent in forces with machine guns and an armored train. This put an end to Heinzenland after just two days. The so-called Republic lacked widespread support. Those who supported it failed to take control of Mattersburg or anywhere else in the region. They were not willing to risk a violent clash for their poorly conceived idea. Propaganda, ruses, and low-level subversion were not going to be enough. This was a political adventure that mercifully ended before anyone lost their life. Faced with serious opposition from the First Hungarian Republic’s forces, the Republic collapsed after just two days. It had been a dangerous idea that made very little sense. Heizenland was over almost before it started.

The Hungarian authorities suspected higher level involvement by the government of German-Austria in the Heizenland affair. The leaders of German-Austria denied any knowledge or involvement with the creation of Heinzenland and distanced themselves from the debacle. There was evidence to the contrary, but Hungary did not pursue the matter for very long. The last thing German-Austria needed was a war with Hungary. Heinzenland turned out to be a small part of a much larger failure. German-Austria’s most important priority was to create a union with Germany. The victorious powers were adamantly opposed to this. The idea went nowhere. Adding millions more Germans to Germany was a non-starter for France and Great Britain.

The Republic of German-Austria soon became the First Austrian Republic. In an ironic twist, West Hungary did become part of Austria. Rather than at the barrel of a gun, it happened with the stroke of a pen when the Treaties of St. Germain-en-Laye and Trianon went into effect. The Republic of Heinzenland was relegated to a footnote in the history books. There was nothing notable about it. Heizenland accomplished nothing other than provoking the Hungarian authorities to take action to put a quick end to it. The Republic had been one in name only. The only notoriety was a lack of longevity.

Same town, different country – Mattersburg after becoming part of Burgenland

A Bizarre Sideshow

Heizenland was one of several forgettable republics that formed and dissolved in the immediate period after World War I. They either disintegrated or were assimilated into larger states. Mattersburg’s role in the affair was as short-lived as Heinzenland. There were more important things for those who lived in the town to worry about. Heinzeland could not solve Austria’s many woes. It was nothing more than a bizarre sideshow that had virtually no chance of succeeding. Heizenland was the product of wild ambition, political machinations, and impulsive declarations. Combined, those were a recipe for complete failure. Heizenland was soon forgotten, as was Mattersburg’s role in. That is except for a few works of history that document the unhappy history of a two-day Austrian affair.

Click here for: Property of a Lady – Elizabeth Bathory & Lockenhaus (Lost Lands #53)