Seven years ago, I drove into the town of Mattersburg in the northern part of Burgenland. My destination was Burg Forchtenstein, a gloomy castle situated upon a slab of dolomite. Mattersburg sits 253 meters below Forchtenstein. I had not given much thought to the town beforehand. Imagining it as nothing more than a place I had to pass through on the way to the star attraction. Winding my way through the neatly kept streets and colorful houses, I felt the allure of small-town life that has been all but lost in America due to suburbanization. Mattersburg was the way I went to remember a town. People with shopping bags strode down the sidewalk, the storefronts were filled with merchandise, park benches were conveniently situated, everything was within walking distance. I was sure gelato lurked less than fifty meters from any place in the town center. What could possibly be better than that. Mattersburg struck me as the kind of place that takes pride in itself. The town was an Austrian version of Norman Rockwell.

I have my doubts about Austria with its oppressive cleanliness, neat freak neuroses, manic precision and people whose silent intensity makes me nervous. What I do not have my doubts about is that Mattersburg presents a pleasing prospect to visitors. I lost myself in a sort of nostalgic revelry for a world that I thought no longer existed and wondered if it ever really did. Mattersburg made a believer out of me. Lost in this revelry were my usual forebodings that a darker history was hidden by the happy face of Austria. I knew that conflict had happened in these small towns, and those events were still within living memory. There were still other similar ones which were not much more than a century old. The pristine image Austria now presents to the world obscures its tumultuous past. Even a provincial town like Mattersburg was not able to escape the maelstrom. In one case, they were at the center of it.

Storm warning – Lightning strikes in Mattersburg

A Bad Marriage – Powerful Versus Pugnacious

I did not learn the post-World War I history of Mattersburg (Mattersdorf until 1924/Nagymarton in Hungarian) until long after my visit. While working on my itinerary for the lost lands beyond Hungary’s borders I came across one of those obscure footnotes of history, the Republic of Heinzeland, that keep me up at night. This led me right back to Mattersburg. The town had played an outsized role in an Austrian attempt to sever West Hungary from the newly formed First Republic of Hungary. This was not all that surprising. During the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Austrian and Hungarians were bound together in the equivalent of a bad marriage where they stayed together for the kids. The marriage dissolved once the kids left home (the empire’s nine other ethnic groups) at the end of World War I. Austria and Hungary then reverted to exchanging pleasantries while subverting one another. Austria had always been the stronger sibling, while Hungary played a pugnacious role. After the war ended, both were in survival mode. Securing the future might come at the expense of a former imperial partner.

Of the two, Austrians had always been the more conniving. They had inherited this trait from centuries of Habsburg rule. The Austrians knew how to stir up unrest among different groups to benefit themselves. If this included their ethnic kin in West Hungary, they were willing to do it. There were violent movements cropping up all over the former empire after the war. Austria was a terrible mess. Famine was stalking the streets of cities, towns, and villages. Hungary, which had been the empire’s breadbasket may have had more food, but their government was weak. Revolution was in the air. Soldiers had come back from the front and were adding to the chaos. They had been militarized in the trenches. Using armed force had become a way of life. Trying to create some sense of order out of this chaos would have taxed the resources of any government. The ones in Austria and Hungary were also trying to figure out their way forward in a world where they were at the mercy of forces beyond their control.

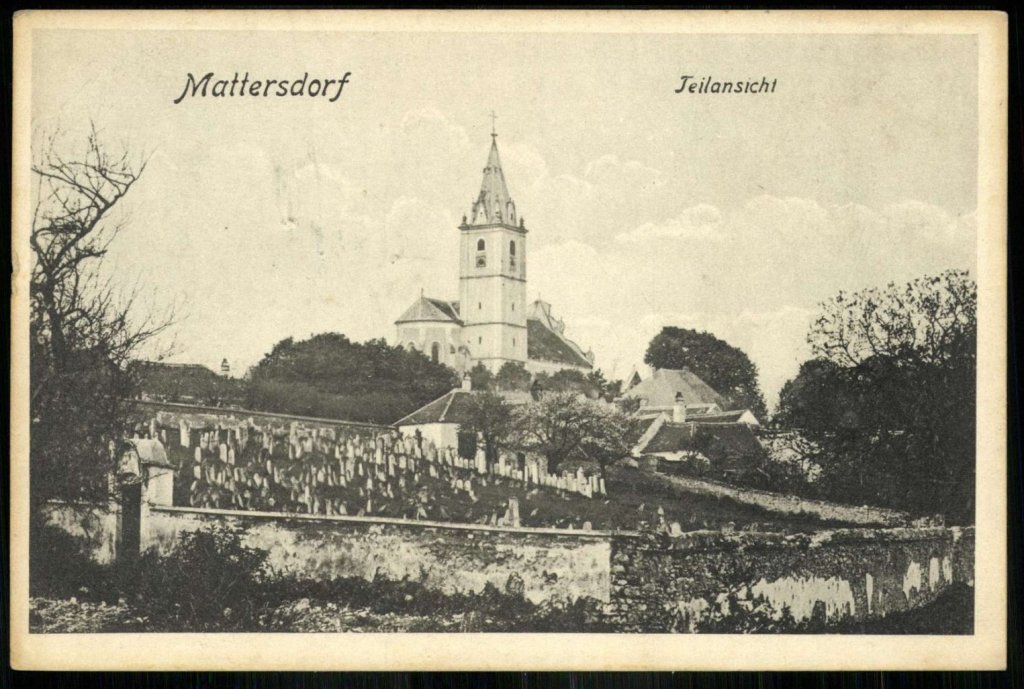

Deceptive calm – Postcard of Mattersburg

Nation Building – Disputed Territory

The Republic of German-Austria. The name sounds like an expression of the obvious. Instead, it was the initial iteration of what was to become the First Austrian Republic. It consisted of the old Austrian Empire’s Alpine and Danubian crownlands. This rump nation needed all the ethnic Germans it could get. The idea was not to create an independent Austrian state, but to instead form a union with Germany. By doing this, the core Austrian lands would safeguard their future by becoming part of a much more powerful Germany. This made sense because if left as a standalone independent state, Austria would be weak and its territory vulnerable to attack from neighboring states filled with ethnic groups it had once ruled over such as Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. The problem was that German-Austria’s leaders were in no position to dictate a union with Germany to the victorious powers who would decide the fate of postwar Europe.

The victors were not about to allow Austria to team up with Germany and create the kind of formidable German state they had just spent four years and the lives of millions defeating. France and Great Britain wanted Germany weakened so that it could not start another war. German-Austria was already weak. Its leaders saw an opportunity in West Hungary to boost their prospects by taking control of the territory. German-Austria could not afford to get into an outright war with Hungary. Their best bet was to stir up unrest among the ethnic German majority who made up two-thirds of the population in West Hungary. Hungarians were only the third largest ethnic group in the region. (Croatians were second). They would have trouble keeping control if there was a groundswell of popular support for the region becoming part of German-Austria. That was not going to be easy.

Tidy town – Mattersburg

Shadow War – A Surreptitious Setup

The First Hungarian Republic was involved in trying to keep territories on its frontiers from breaking away. To that end they sent officials from the Hungarian National Council into West Hungary to make sure this did not happen. Opposing them was the Westungarische Kanzlei (West Hungary Council) setup surreptitiously by officials in the Republic of German-Austria to lobby ethnic Germans into breaking away from Hungarian rule. Ground zero for this movement would become Mattersburg, the place that was soon to be identified with the Republic of Heinzeland.

Coming soon: A Two-Day Austrian Affair – The Hopelessness of Heizenland (Lost Lands #52c)