In January an academic conference on the Treaty of Trianon was held in Budapest. Though the 100th anniversary of the treaty’s signing occurred in 2020, Trianon is still of such intense interest among Hungarians that the topic never fails to draw an audience. Of the nine presentations given at the conference, five were on relations between Hungary and Romania. This was not a coincidence. I have talked with many Hungarians about Trianon and heard a range of opinions. There is a sense of resignation in every Hungarian I have spoken to about it. One told me it was the second worst thing to happen in world history, ranking only behind the Holocaust.

Another Hungarian told me she didn’t care about Trianon. That same woman mentioned that her surname came from a village in Eastern Transylvania where her family originated from. I looked up the village on a map and discovered that it was right on the pre-Trianon border between Austria-Hungary and Romania. One Hungarian told me the victorious powers were to blame for the treaty. They loathed Hungary and wanted to dismember the country. Every Hungarian seems to have an opinion about Trianon. The one place they most often mentioned while discussing Trianon was Transylvania. This is why I put Romania first on my itinerary for the lost lands beyond Hungary’s borders.

The long view – Reformed Church & Ghenci village in Crisana (Credit: Ady Negrean)

Land of Confusion – Far From The Truth

Contrary to popular belief, Transylvania is not Dracula. Blood thirsty vampires do not lurk in the dark recesses of ominous castles. For centuries, vampires enjoyed legendary status among Transylvanian peasants. Bram Stoker took those legends and created a character that haunted the imagination of readers all over the world. Dracula and vampires are a distraction from the real ghosts of Transylvania. Those ghosts enter the room when Transylvania and Trianon are discussed. Hungarians and Romanians are haunted by the ghosts of Trianon. For Romanians, the ghosts are mostly friendly, For Hungarians, the ghosts are always tragic. As a foreigner, I find these extremes disconcerting. They remind me of a line in T.S. Eliot’s poem Ash Wednesday, “Wavering between the profit and the loss. In this brief transit where the dreams cross.” Dreams certainly cross the Hungary and Romania border. As do nightmares.

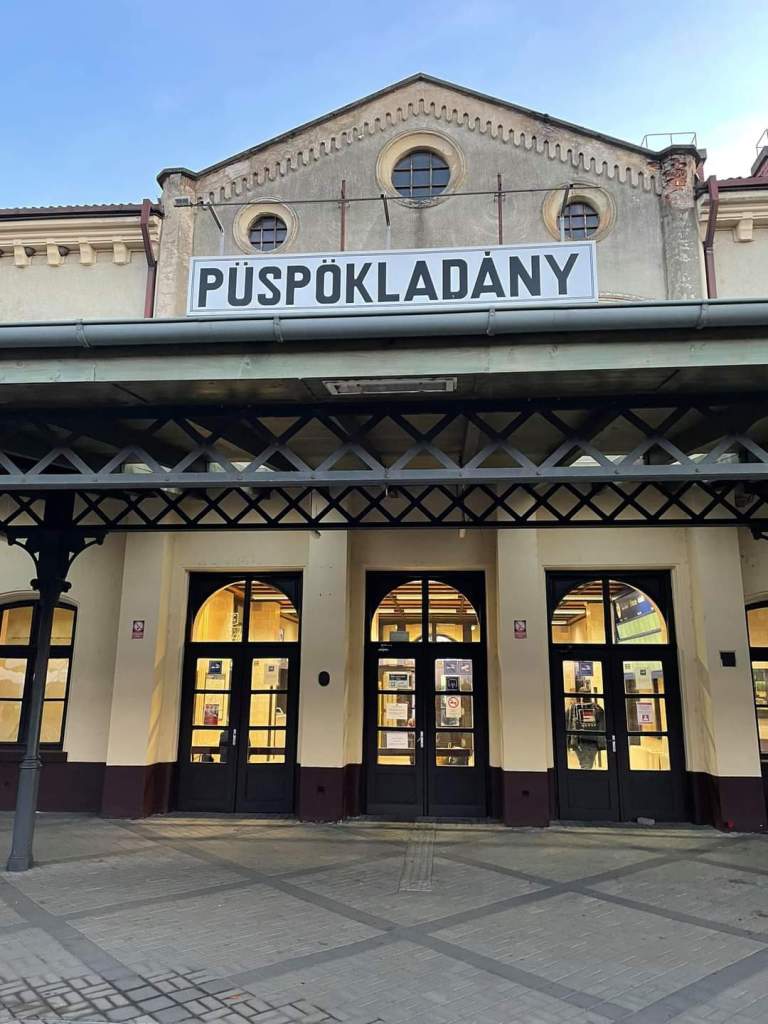

Listening to Hungarians talk about Transylvania can make you believe the region is right across the border in Romania. It is as though you could reach out and touch it. This is far from the truth. To get to Transylvania, one must first cross the Hungary-Romania border, then make their way across a land of confusion. This is the Crisana (Körösvidék) Region. I have yet to hear a single person call the region by that name. Transylvania literally translated means the “land beyond the forest.” Crisana should be known as the “land before Transylvania.” Crisana’s claim to urban fame is the beautiful city of Oradea (Nagyvarad). Though the landscape of Transylvania is nowhere in sight, Oradea is often wrongly placed in the region.

Splitting the difference – Crișana Region in Hungary and Romania (Credit: The Blue Mapper)

Caught In The Middle – Splitting The Difference

I did a Google search for the question, “Is Oradea in Transylvania?” The second result yielded by the search came from that long-trusted source of knowledge Britannica. The listing said, “Oradea | Cities, Transylvania, Hungary.” I guess the best and brightest are not always correct. Travelers will also be wrong footed by the open-source travel guide Wikivoyage. The second sentence of its Oradea entry begins, “Despite the city being one of the largest and most important in Transylvania…” For all those who decry Wikipedia as a less than trustworthy source, they might want to think again. The first sentence of its entry on Oradea points the reader in the right direction, stating that Oradea is “located in the Crisana Region.” It is also one of the most beautiful cities in the lost lands.

For the pedants among us, let us state for the record that Crisana gets its name from the Cris (Koros) River and its three tributaries. One of those tributaries, the Crisul Repede runs through the heart of Oradea. The boundaries of Crisana stretch into eastern Hungary and include the country’s second largest city, Debrecen. Crisana is as much a land unto itself as Transylvania. While it lacks the spectacular natural beauty found in the latter, it does include a multitude of landscapes from pastoral flatlands, verdant forests, and foothills that roll away towards the mountains. All of this is lost on the traveler who is entranced by visions of Transylvania. That is a shame because Crisana rewards those who let their curiosity guide them. There could be worse things than the Romanian part of Crisana being placed in Transylvania, but hardly more absurd ones. It is a wild exaggeration. Just how wild can be shown with a thought experiment.

Natural setting – Sunset in Crisana (Credit: Adrian Padurariu)

Farmer Harker – Dracula In Crisana

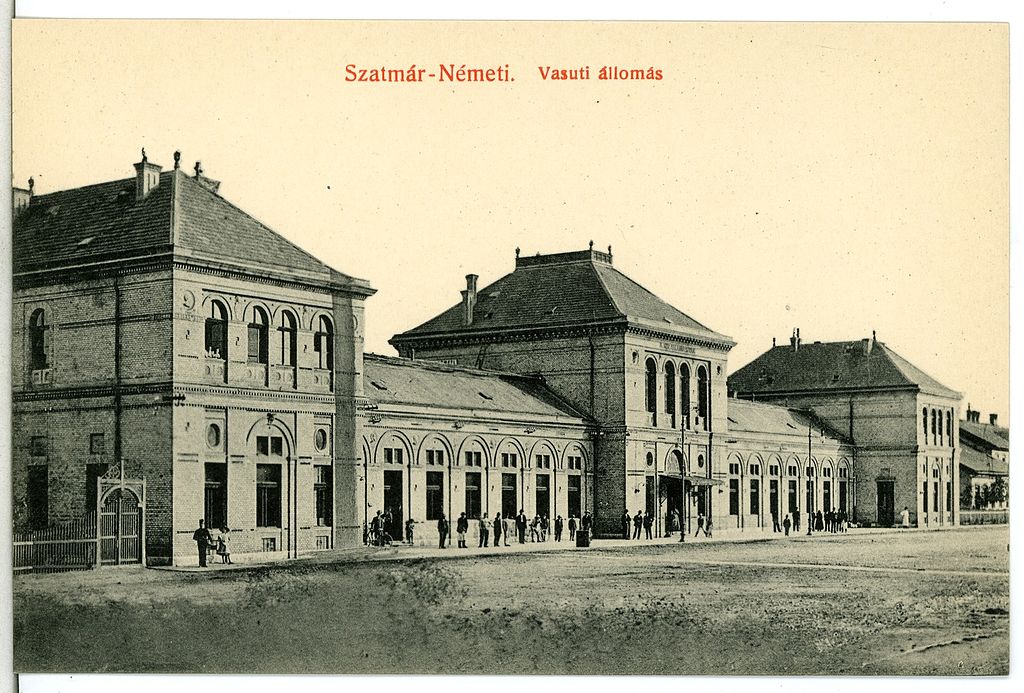

Imagine Bram Stoker’s Dracula inhabiting a gloomy manor house surrounded by farmland. Rather than wolves, docile horses and wandering cattle doze in the surrounding fields. The only battlements to be found are stalks of wheat and corn. Jonathan Harker has come to help Dracula sell his estate to a ginormous agricultural corporation that lives off massive subsidies from the European Union. Dracula’s devious plan involves getting back at Harker who he sees as all that is wrong with the EU. Dracula blames Harker and useful idiots like him for ending the era of the wooden plow. Rather than a shadowy coachman coming to pick up Harker upon his arrival at the railway station in Satu Mare, a couple of Securitate agents driving a horse drawn wagon cart show up to collect him.

Much to his detriment, Harker discovers that Dracula sucks less blood than the summertime mosquitoes. Harker spends his time writing scathing letters back to the love of his life in London. The fact that the Count’s estate is not in Transylvania drives him nearly mad. How can this be the land beyond the forest when he has yet to reach it? Harker never notices Dracula’s sinister intent as he becomes obsessed with the vagaries of animal husbandry. Harker saves himself from an even worse fate by chasing the Count off the property and into Transylvania with a John Deere tractor. Everyone lives happily ever after. Such is life in the lost lands. I cannot wait to see what comes next in the land beyond the Hungary-Romania border.

Click here for: Stepping Over The Line – Hungary-Romania Border (The Lost Lands #4)