If you ever want to amuse yourself with a slightly sadistic activity, I highly recommend the travel journey planning website Rome2Rio. Type in your points of departure and arrival, then wait for a couple of seconds as the website works its magic. The site will give you train, bus, and car options to any destination they desire. These can be a source of fascination, especially when transfers are involved. Any search between two places that cannot be reached with a non-stop service will result in numerous options, some of which are scarcely viable unless you are willing to endure extreme fatigue.

I found one particularly exhausting option while searching for the most efficient way to travel between Uzhhorod and Oradea for my Lost Cities beyond the Hungarian border itinerary. There is no non-stop train service between the two cities. The fun really began as I looked through the options that were offered. One that got my attention was “Train via Biharkeresztes” because it offered the shortest travel time. I did not have the slightest idea of where Biharkeresztes was located other than in Hungary. Clicking on the option revealed a nightmarish itinerary that made me want to book my tickets just to see if I was up to the challenge.

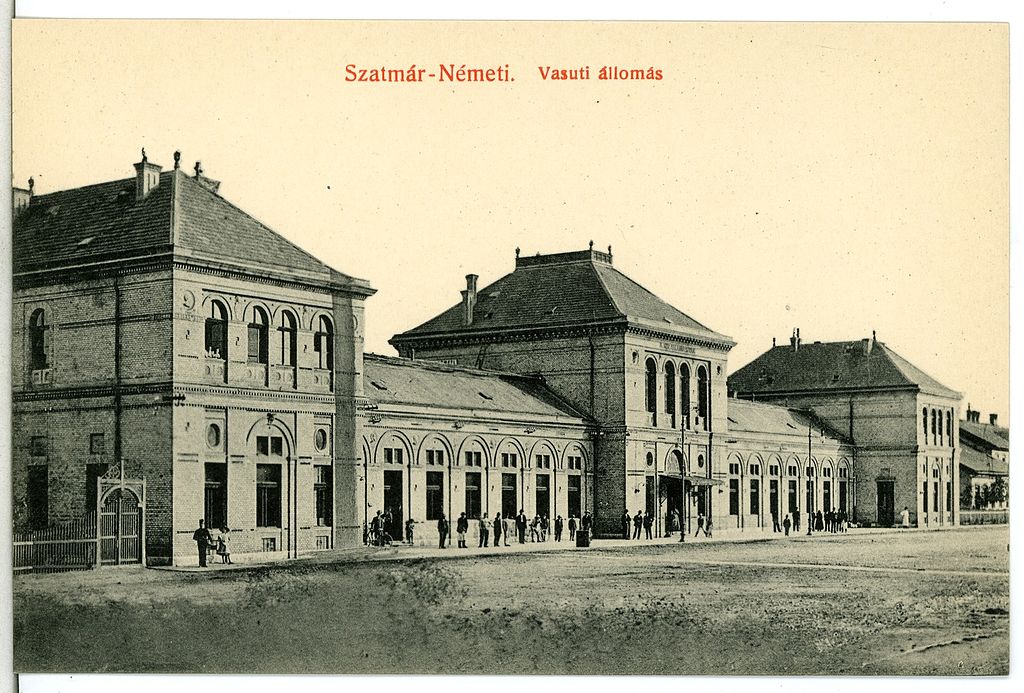

On-time arrival – Train from Puspokladany arriving in Oradea (Credit: Boldizsar Sipos)

Beyond Midnight – Ready For Departure

My fascination with a potential journey via Biharkeresztes began when Rome2Rio showed that it would take eight hours. I sighed. While I expected a lengthy travel time due to the lack of a direct connection between Uzhhorod and Oradea, seeing an eight-hour journey listed as the first option, made me realize the difficulty of getting between the two cities in a timely manner. There was no getting around the fact that this leg of my itinerary would take most of a day. Little did I know that the time given did not include transfers and waiting at stations. When I investigated the option further, I saw that the entire trip would take 14 hours and 14 minutes. I was astonished to learn that the details revealed the trip would be even tougher than the amount of time it took. I would spend two-fifths of the time waiting in stations, part of it in the dead of night at a station in the Hungarian town of Puspokladany.

Public transport stations late at night and in the earliest hours of the morning are something I generally avoid while traveling in Eastern Europe. For that matter, I try to avoid them anywhere I travel in western Europe or America. A railway or bus station around midnight or thereafter is an invitation for trouble. While I have never noticed any violent criminal element in the evening at stations I have frequented in Eastern Europe, the possibility is always there. After the sun goes down, there is usually a noticeable increase of seedy characters that look ready to commit petty theft at stations. In my opinion, they are more of a danger to someone’s belongings than they are to passengers, but why tempt fate unless it is absolutely necessary. My late-night experiences at stations are limited so I am no authority on the matter. The most memorable of these turned out to be completely benign.

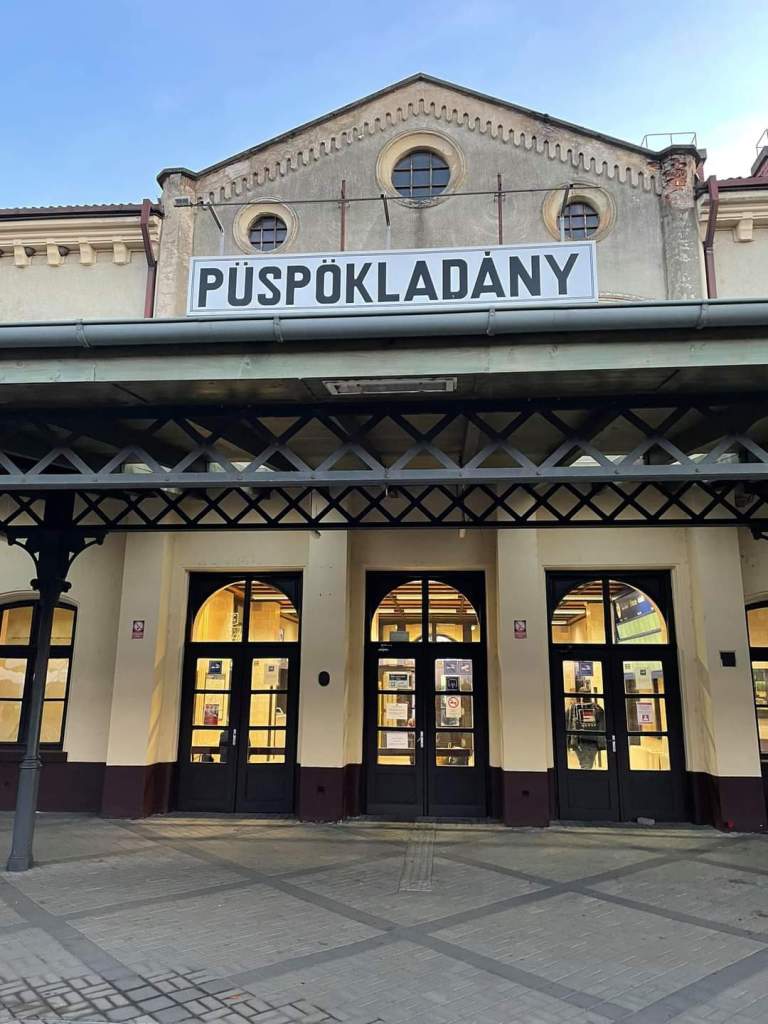

Awaiting arrivals – Puspokladany Train Station (Credit: Tony Fekete)

Nocturnal Travel – A Marathon Journey

I arrived not long before midnight on my first visit to Lviv in western Ukraine. I went into the main hall expecting it to be deserted. Instead, I found a large crowd awaiting arrivals or departures. The worst thing I encountered on that occasion were the taxi drivers. In Eastern Europe, it does not matter if it is morning, noon, or midnight, the taxi drivers are always prepared to fleece foreigners. They haunt arrival areas in railway and bus stations waiting to confront bleary eyed travelers. In Lviv, the taxi drivers were no real danger to anything other than my wallet. Despite coming through this experience unscathed, I am still reluctant to take my chances by hanging around in a public transport station late at night. Nonetheless, this is sometimes unavoidable. For example, the journey from Uzhhorod to Oradea.

If I was to take the timeliest train option that Rome2Rio provided me, I would find myself waiting in a railway station late at night. The marathon journey begins at Uzhhorod in the late afternoon. That time of departure is never a good sign if you are traveling across three countries with three different languages while navigating two border crossings. This would surely be enough to induce plenty of stress. That might help me stay awake during what would be a long day’s journey deep into the night. One positive would be gaining an hour after crossing into a different time zone from Ukraine to Hungary. One negative would be losing that same hour after crossing from Hungary into Romania. Traveling is never easy in the remoter reaches of Eastern Europe. The toughest part comes when making a transfer at Puspokladany in eastern Hungary. The problem is that the train arrives there at 8:33 p.m. followed by a four and a half hour wait. I have made transfers at Puspokladany before. The station is in excellent condition and safe. Still, spending a considerable amount of time there long into the night is less than ideal.

Somewhere down the line – Beside the platform at Puspokladany (Credit: Tony Fekete)

On-Time Arrival – Before The Break of Dawn

The train from Puspokladany to Oradea does not leave until 1:01 a.m. This is a sleeper train traveling between Budapest and Brasov. I would be at risk of falling asleep on this train. There are worse things in travel than missing a long-awaited stop and waking up in Transylvania. One of them happens to be trying to stay awake all the way to Oradea where the train arrives at 4:17 a.m. That just might be late enough that all the miscreants and ne’er do wells have either passed out, stolen their quota of cigarettes, or gone to bed. I would be left searching for a bed of my own while wandering the streets of Oradea a couple of hours before dawn. Is there anything worse than those final hours of the early morning before dawn? I am not sure, but I intend to find out. This might not sound like fun, but it is an adventure.

Click here for: Whisper To A Scream – The Door In Nagyvarad (The Lost Cities #7)