Burgenland is like the person who gets invited to dinner and the guests forget they are there. After the meal is finished someone out of politeness finally asks them a question and is perplexed by the answer. The guests mutter to themselves, “what are they doing here?” No one answers and everyone goes back to ignoring them. Burgenland is the unexpected guest who is happy to never call attention to themselves. It does not ask for attention and affirmation. Burgenland is one of those places that does not make sense and somehow still does. It is the Austrian equivalent of the middle of nowhere. And for me, nowhere is the place to go.

Ideal setting – District of Oberwart in Burgenland (Credit: Zeitblick)

Becoming Burgenland – Bordering On War

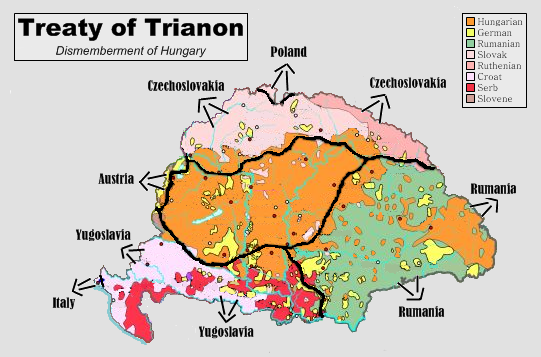

Burgenland’s creation was improbable. I find that to be one of its most attractive traits. The phrase, “you can’t make this stuff up” comes to mind. As a province, Burgenland never existed prior to the birth of Austria. It was cobbled together from the counties of Moson, Vas, and Sopron that had been in the Kingdom of Hungary. The name was contrived and to a certain extent so was its territory, but there was a certain logic to its creation. Two-thirds of the inhabitants in the 1910 Austro-Hungarian census of the region that would become Burgenland were German speakers. They were the descendants of ethnic Germans who migrated to the area in several waves over the previous 500 years. Putting them in Austria was logical. Hungary was not happy with the creation of Burgenland. They were in no position to do much about it, but that would not stop some nationalists from trying.

Burgenland became another of the lost lands beyond Hungary’s borders. This was grudgingly accepted, but a backlash led to an uprising in West Hungary. The result would be Hungary gaining the city of Sopron and its outlying area through a plebiscite. The rest of Burgenland would remain as the eastern extremity of Austria. Burgenland would become a borderland in more ways than one. How many provinces can say that they share a border with three different countries, two of which – Slovenia and Slovakia – have a shorter existence than Burgenland. Like many borderlands, Burgenland was also a source of conflict during its birth. Two failed states arose there after World War I, the Republic of Heinzenland and Lajtabansag (Banate of Leitha). Burgenland might have been a backwater, but many of the inhabitants felt the land was worth fighting for.

Putting together the pieces – Burgenland’s Districts

Flip Sides – Going In Reverse

On a map, Burgenland looks like it was thrown together from disjointed parts grafted onto each other. There is a symmetry to this that involves a geographical role reversal. Burgenland was the flip side of the same coin for Austria and Hungary. It was the westernmost part of the Kingdom of Hungary before it then became the easternmost extent of Austria. For the longest stretches of its history, Hungary administered the region, but Hungarians were never the majority ethnic group. In the early 20th century, ethnic Germans outnumbered Hungarians eight to one. Astonishingly, ethnic Croatians also outnumbered Hungarians by almost two to one. Hungarians either owned large-landed estates, acted as border guards or were bureaucrats. This meager Hungarian presence made Burgenland an easy grab for the treaty makers as they created Austria. While this ended up working out, it is hard not to feel that there was a make it up as you go mentality.

Burgenland has a strong north-south orientation (166 kilometers) and a weak east-west one. It is much longer than it is wide. A traveler who wants to keep within the borders will inevitably find themselves going either north or south. The slenderest portion of the province is only five kilometers in width. That narrowness has presented problems in the past. During the Cold War, trains heading either north or south at one point would cross into Hungary. The doors were sealed so no one could leave the train while it transited this Iron Curtain corridor. Today, that is no longer a problem since Austria and Hungary are both in the Schengen Zone. I know from experience that it is easy to get around Burgenland despite its strange geography. It is helpful to remember that Burgenland’s shape was the product of a peace conference. That makes it easier to understand why it looks so strange on a map. This can be of benefit to the traveler.

Gloom & room – Courtyard at Burg Lockenhaus (Credit: Monyesz)

Casting Shadows – Gloom & Room

There are very few places with such a long and unique history that a traveler can cover in a couple of days or less. Burgenland is one of them. Driving the entire province from north to south takes as little as three hours. For those who want to see more, nothing is ever far off the beaten path. A comprehensive trip can cover Burgenland’s seven districts in less time than it takes to visit three or four museums in Vienna. It is bound to be more relaxing. Burgenland may be Austria’s smallest province, but it is also the least populated. Time moves to the rhythm of rural life. This allows for visiting the most important historic places at a leisurely pace. There are a couple of can’t miss castles for very different reasons. These are Burg Forchtenstein and Burg Lockenhaus. The former is associated with the Esterhazy’s, the pro-Habsburg Hungarian noble family par excellence whose splendid palace also adorns Eisenstadt.

Lockenhaus casts a much darker historical shadow as it is one of Elizabeth Bathory’s old haunts. Putting her name with the place is bound to get attention as the infamous Blood Countess was reputedly the worst female serial killer in history, though that is open to debate. After contemplating Bathory’s exploits, everyone is bound to need a break. Burgenland’s diverse landscapes provide that. In the north, flat and rolling farmland predominates. The further south one travels, the hillier and more forested the terrain. Forchtenstein feels positively gloomy, perched on an outcropping of dolomite. In the southern reaches of Burgenland lies the warmest area of Austria. Positively balmy compared to the country’s Alpine areas. By this point, the traveler should have a good understanding of Burgenland’s geography and an idea of its history. Few travel the length of this lost land, but those who do will never forget it. Burgenland is nothing if not memorable. If only more people knew that.

Click here for: A Tale of Political Adventure – Heinzenland (The Lost Lands #52)